This week, residents in three Vancouver neighborhoods start tracking their food consumption, waste patterns, and transportation habits for 14 days. They’ll repeat the same exercise one year from now. Their goal: reduce their Ecological Footprint by at least 15 percent over the course of the year to help Vancouver move closer to its goal of reducing the city’s overall Ecological Footprint by 33 percent by 2020.

“The city of Vancouver helped us pick the neighborhoods, including a high-rise community with many renters,” explains Robyn Chan, Green Bloc Project Coordinator at Evergreen, a Canadian nonprofit that specializes in public engagement projects to advance green urban living.

“The Ecological Footprint is a great tool for engagement,” she says. “I don’t know what carbon looks like, but I know how many planets we have!”

A pilot project that ran between 2013 and 2015 in a neighborhood of single-family homes and became the foundation of the Green Bloc Program yielded a 12% Footprint reduction.

A fourth neighborhood is slated to join the project soon.

Greenest City 2020 Action Plan

Vancouver residents have an Ecological Footprint three times larger than what is available per person worldwide. In 2011, the city announced its goal to reduce its Ecological Footprint by 33% below 2006 levels by 2020 and achieve one-planet living by 2050. It doubled down on its commitment in 2015, with a goal of zero waste/zero carbon by 2020. Last July, the Vancouver City Council passed the Zero-Emission Building Plan. The city also started reaching out to key players in the private sector, including hotels, retailers, and real-estate developers.

On the citizen engagement front, the city gave Evergreen a $25,000 grant to create the Green Bloc Program last year. In 2017, a $50,000 grant supports the Green Bloc Project in three (possibly four) neighborhoods.

“We work closely with the city to track specific data. They remain involved at all stages of the Green Bloc Project, which adds to the legitimacy of what we do, and helps us connect our action to the bigger picture,” Chan points out.

Some 25 residents attended the first workshop that kicked off the project last week. Dr. Jennie Moore, director of sustainable development and environmental stewardship at British Columbia Institute of Technology’s School of Construction and the Environment, presented the Ecological Footprint and the concept of one-planet living to the group.

Calculating households’ Ecological Footprints

Together with her master’s and PhD supervisor University of British Colombia Professor Bill Rees—who co-created the Ecological Footprint with Footprint Network co-founder Mathis Wackernagel—Moore has been working closely with the city of Vancouver to achieve the lighter footprint targets of the Greenest City Action Plan. Her bottom-up approach to calculating urban metabolism builds on households’ Ecological Footprints, whose assessment is rooted in a two-week or four-week survey that Moore originally developed with two other PhD students under Reese, Cornelia Sussman and Meidad Kissinger, working with Evergreen.

Besides providing energy consumption (electricity and natural gas), and train and air travel data for the past 12 months, households who choose to participate keep track of the food they eat and how they get around (driving, biking, public transportation) each day—a 15- to 25-minute task according to the organizers. Each week, they also report how much waste they generated (by weight).

Last week’s workshop gave participants the opportunity for a lively brainstorming session to identify goals in terms of Ecological Footprint reduction, including at the neighborhood scale.

Evergreen has already defined how it intends to use the Green Bloc Project this year to advance its urban sustainability agenda: Work with the city of Vancouver to lower barriers to entry for new projects (including simplifying permitting for urban edible gardens), and train individuals to manage community projects.

“We’re thrilled that the city is already investing in a high-rise, lower-income neighborhood, per our past recommendation,” say Chan. “At Evergreen, we hope to expand the program to other neighborhoods, and even to other cities in Canada,” she adds.

Steps forward

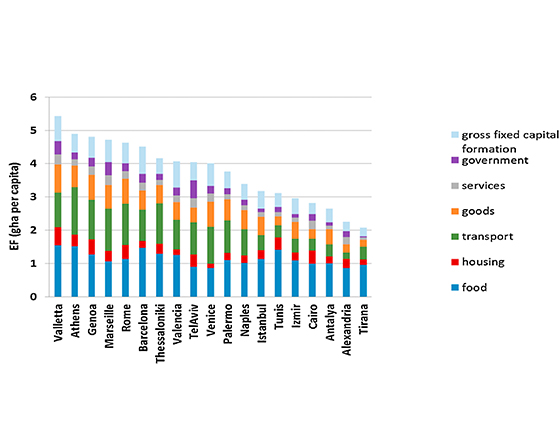

Meanwhile, Vancouver is taking steps to improve its Ecological Footprint calculation. Food makes up the biggest component of Vancouver’s Ecological Footprint, followed by buildings and transportation. This year, the city is funding a program to collect food provisioning data from local farmers’ markets, community gardens, and local food retailers, with a view to using accurate local food data instead of national data in its Footprint calculation.

The city also has announced the creation of 2,020 garden plots for households by 2020, and is promoting local, seasonal foods through farmers’ markets.

According to Moore, Vancouver has been addressing urban sustainability from a demand-side management approach since at least 2000. “Kudos to them for committing to very ambitious goals. Reaching 33% by 2020, however, is going to take much bigger efforts,” she says.