If everyone on Earth lived the lifestyle of the Cloughjordan Ecovillage, we would be remarkably close to living within the budget of our planet’s ecological resources. Researcher Vince Carragher’s bottom-up Ecological Footprint accounting methodology helps residents stay on track.

Seven years after construction started in the middle of Ireland, Cloughjordan Ecovillage counts 54 homes. Its solar- and wood-powered community heating system is up and running, as are the wood-oven bakery and the eco-hostel for visitors. The organic, bio-dynamic community farm, one of the largest community-supported agriculture (CSA) schemes in Ireland, caters to over 60 families; it can serve 80 when operating at full capacity.

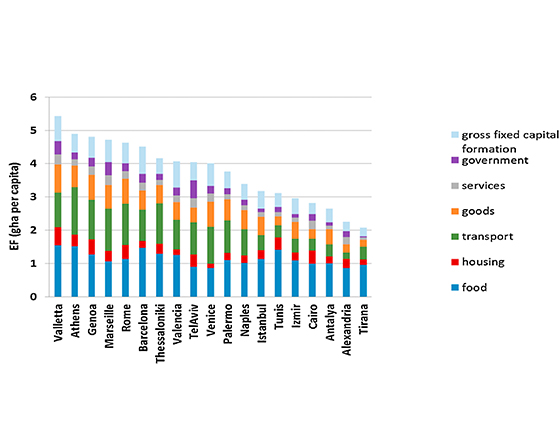

Cloughjordan Ecovillage residents have an average Ecological Footprint per capita of only 2 global hectares (gha), according to the first Ecological Footprint survey of residents that was carried out last spring and presented to the community in November. By way of comparison, Global Footprint Network estimates that the average amount of biocapacity that is available per person on the planet is 1.7 gha.

The survey was conducted by Vincent Carragher, energy manager and research coordinator at Tipperary Energy Agency and an expert on local scale material and resource flow analysis and decarbonisation. His bottom-up approach, which he developed during his doctorate research on Ballina, an Irish community of 700 households, focuses on data collected directly from each household. It is based on the original Ecological Footprint accounting methodology developed by Mathis Wackernagel, now president of Global Footprint Network, and William Rees at the University of British Columbia, and other subsequent works.

The original methodology developed by Wackernagel and Rees calculates the Ecological Footprint based on national economic data on consumption and land use, then divides it by the number of residents to obtain the Ecological Footprint per capita. According to this approach implemented by Global Footprint Network, the average Ecological Footprint of an Irish resident is 5.5 gha – more than double that of the average Cloughjordan ecovillager as calculated with a bottom-up methodology.

“There is strong merit in the top-down approach developed by Mathis, and my major adaptation to that was to develop a locally-based, bottom-up method which sampled and reflected consumption differences at the local level,” Carragher explained.

“The huge advantage of the bottom-up approach is that it points to individual responsibility,” he told Global Footprint Network. “As such it is a tool for educating local communities and individual households, since they feel fully responsible for their Ecological Footprint and can see the impact of modifying their behavior to live more sustainably,” he added.

In this respect, Carragher and Cloughjordan Ecovillage are only getting started. “What I have released so far are the results for the average ecovillager. But it is of note that there is massive divergence within consumption categories, so [CO2] waste emissions of one person might be 10 times those of another, and this goes for all consumption categories,” Carragher said.

The Ecovillage residents are truly engaged with the process. The Ecological Footprint survey scored a response rate of 94 percent (47 of the 50 households living in the village last spring participated). And at the request of many residents, Carragher is now working on establishing the specific Ecological Footprint of each household.

Identifying individual consumption patterns will help each household focus on a tailored plan to reduce their Ecological Footprint through collaborative support and shared best practices.

“[The Footprint survey] provided an opportunity to quantify other areas of our daily lives which we hadn’t measured before—namely transport, waste and food,” resident Deirdre O’Brolchain told Global Footprint Network in an email. “Whilst our household liked to think that we were ‘eco-nscientious’ in these three areas, the survey reminded us that we’ve loads of room to improve – and that is our challenge over the coming year, and before we complete the next Ecological Footprint survey,” she continued.

The concept of Cloughjordan Ecovillage in Ireland was first sown in the 1990s. The site was acquired in 2005. Outline planning permission was granted two years later for 114 homes and 16 live/work units on 67 acres to the north of historical Cloughjordan in County Tipperary. The first residents moved into their homes in December 2009.

“People were looking especially at a more sustainable approach to food production than they could find or develop in a city,” says Carragher.

His approach to calculating the Ecological Footprint of food relies heavily on the energy used in food production (“embodied energy”) and methane emissions caused by animal farming. As such, the survey asked households to provide data related to their diet in order to evaluate their consumption of plant-based foods and animal-based foods (the latter being more resource and energy intensive). Incorporating the Ecological Footprint of non-local food consumed in the village, on the other hand, remains one of the stickiest methodology challenges, mostly due to the difficulty of tracking such data from households.

Although incomplete, the current food Ecological Footprint approach still provides reliable metrics, Carragher said. For all its recent popularity, “local food does not significantly lower the carbon and energy intensity of food,” he pointed out.

Carragher remains optimistic about further progress. He was successful in helping Ballina reduce its carbon footprint by 28 percent over four years. And he’s hopeful that the methodology that he’s been applying in Cloughjordan Ecovillage can benefit many other communities across Ireland and beyond.

Additional Resources

The Irish Times: “Cloughjordan: Inside Ireland’s only ecovillage. Estate has survived recession and teething problems; now it’s gaining European acclaim,” Dec. 11, 2015