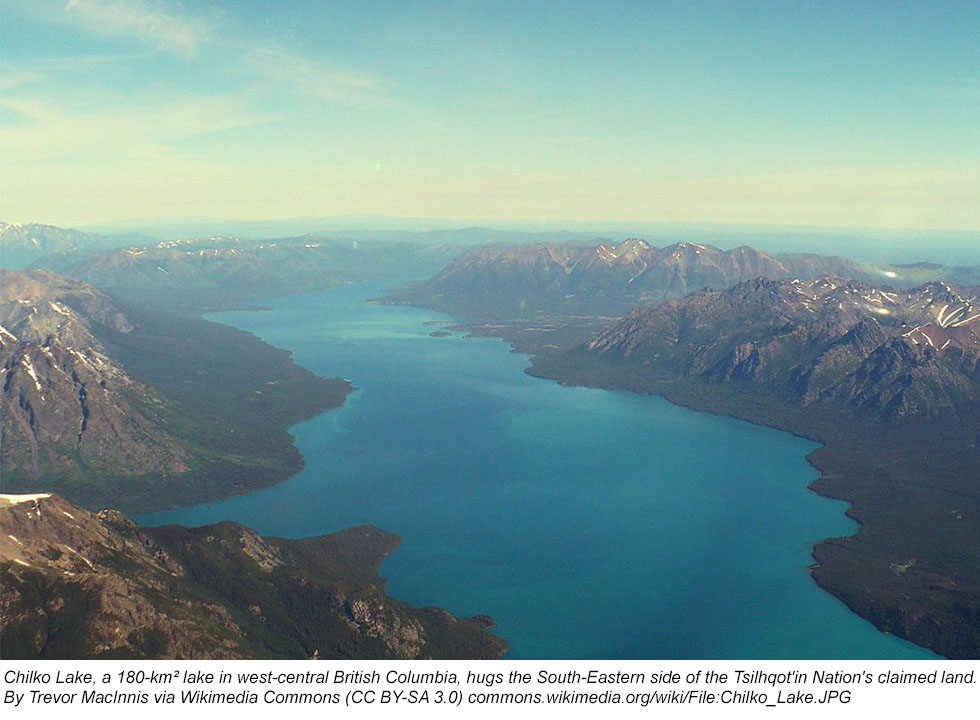

In a first for the Ecological Footprint and a native group in Canada, the Supreme Court of Canada supported the Tsilhqot’in Nation’s title over 1,900 square kilometers in British Columbia as part of a landmark decision announced in June.

The historic ruling came about a decade after Tsilhqot’in Nation’s lawyers called Global Footprint Network to provide an expert study for the case, which centered on clear-cut logging permits granted by the British Columbia government without consulting the native community living on the affected land.

The government defended the so-called terra-nullis (“nobody’s land”) hypothesis—the assumption that pre-European Canada was a vast and empty land—and argued that the First Nation’s title claimed was “too large.”

The challenge that the Tsilhqot’in Nation posed to Global Footprint Network: provide a scientifically sound evaluation of the capacity of the land to support the native group around 1800, prior to European influence and trade.

Global Footprint Network researchers approached the problem from several angles. One was to study the Ecological Footprint of the current population of bears living on the territory. The theory was that the findings about these omnivorous animals that compete for the same food niche as humans could be used to extrapolate the Ecological Footprint of a human group living off the same land.

Global Footprint Network researchers approached the problem from several angles. One was to study the Ecological Footprint of the current population of bears living on the territory. The theory was that the findings about these omnivorous animals that compete for the same food niche as humans could be used to extrapolate the Ecological Footprint of a human group living off the same land.

A second angle involved studying the current local population of wild horses as a proxy for the hooved animals that would make up the main source of animal proteins for the people. And a third approach used anthropological accounts to study the general food habits of the aboriginal population to evaluate how much food they would gather, how much they would store, and what the impact of living on the edge was.

Global Footprint Network’s research findings converged to the conclusion that the claimed area had the capacity to support between 100 and 1,000 people – in other words, that this entire area was needed to meet the needs of the smallish nation – given their traditional hunter gatherer lifestyle. Their Footprint was both wide and light, meaning that it required a wide area given the small volume of natural resources harvested per hectare. Such a Footprint benefits biodiversity, ensuring that the natural capital can regenerate and thrive.

Global Footprint Network was able to show that, at best, terra nullis was an erroneous concept sustained over centuries, ignoring the physical reality of the resource flows supporting populations.

For the very first time, the legal pundits acknowledged this physical reality. “My argument was accepted by consensus by both sides of the case. In fact, I didn’t even have to appear in court to testify since there was no need for cross-examination,” said Mathis Wackernagel, president of Global Footprint Network and lead author of the research report.

After arguing the case in the Supreme Court in November, Jack Woodward, the lead lawyer representing the Tsilhqot’in Nations, wrote Wackernagel, “We simply stated that because of the climate and geography of the area, only a limited number of people could sustainably live in the area, citing the expert opinion report you prepared for us many years ago.”

The historical ruling that followed on June 26 gives the Tsilhqot’in Nation “the right to use and control the land and to reap the benefits flowing from it.”

If you want to learn more about Tsilhqot’in Nation v. The Queen, 2014 SCC 44:

If you want to learn more about Tsilhqot’in Nation v. The Queen, 2014 SCC 44:

The Tsilhqot’in’s legal battles began in the 1980s over clear-cut logging permits that were granted by the government of British Columbia without any consultation with the native community living on the affected land. The B.C. Supreme Court issued a non-binding ruling stating that the Tsilhqot’in probably had Aboriginal title over the land, and that the Crown ought to negotiate a fair and honorable settlement. The federal and B.C. governments appealed the ruling to the B.C. Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court of Canada.

Last November, Mathis Wackernagel, president of Global Footprint Network and lead author of the research report, received this update from Jack Woodward, the lead lawyer representing the Tsilhqot’in Nation:

The court case you helped us on a decade ago finally has wound its way through the levels of court. We had a 339 day trial, then a lengthy appeal to the B.C. Court of Appeal, and last week it was heard on final appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada. In the brief oral submissions (only one hour is allowed to our side at that level of court) your name was mentioned in connection with the “carrying capacity” of the land of the Tsilhqot’in people. This was to counter the position of the Crown that the area for which aboriginal title was claimed was “too large”. We simply stated that because of the climate and geography of the area, only a limited number of people could sustainably live in the area, citing the expert opinion report you prepared for us many years ago. (…) We should get a decision on that appeal in about six months.

As it turns out, “my testimony was accepted by consensus by both sides of the case,” Dr. Wackernagel says.

Paragraph 37 of the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in the case of Tsilhqot’in Nation v. The Queen, 2014 SCC 44, reads:

[37] Sufficiency of occupation is a context-specific inquiry. “[O]ccupation may be established in a variety of ways, ranging from the construction of dwellings through cultivation and enclosure of fields to regular use of definite tracts of land for hunting, fishing or otherwise exploiting its resources” (Delgamuukw, at para. 149). The intensity and frequency of the use may vary with the characteristics of the Aboriginal group asserting title and the character of the land over which title is asserted. Here, for example, the land, while extensive, was harsh and was capable of supporting only 100 to 1,000 people. The fact that the Aboriginal group was only about 400 people must be considered in the context of the carrying capacity of the land in determining whether regular use of definite tracts of land is made out. [Emphasis added.]

Aboriginal rights are protected by the Constitution of Canada. These include the rights to hunt, fish and trap. Although various court decisions have upheld them in recent years, the courts have typically stopped short of declaring land ownership of First Nations over the territories where they exercise their Aboriginal rights.

Until now, that is. The historical ruling gives the Tsilhqot’in Nation “the right to use and control the land and to reap the benefits flowing from it.”

“The law in Canada is leaning towards an ecological interpretation of constitutionally-protected Aboriginal rights so that they are not merely sterile or formal rights, but reality-based and scientifically supported,” Jack Woodward told us. “For example, protection of sufficient habitat to produce a sustainable harvestable surplus is the measure of whether the government has fulfilled its responsibilities to afford sufficient access to fish and wildlife harvesting rights.”

In its first-of-a-kind decision, the Supreme Court of Canada emphasized that obtaining the consent of the native group affected by resource-management decisions within their land, whether before or after a declaration of Aboriginal title, would allow governments and individuals to avoid a legal infringement.

“Today is a new day,” declared Grand Chief Stewart Phillip of the B.C. Union of Chiefs, speaking in Vancouver on the day the Supreme Court’s ruling was announced. “We are in an entirely different ballgame. We’re moving away from the world of mere consultation into a world of consent.”

Indeed, the Supreme Court effectively raised overnight the significance of native groups in decision-making processes, in conformity with the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples which calls for the free prior and informed consent before development on indigenous lands (it should be noted that Canada voted against it.)

At the end of the day, First Nations currently fighting legal battles against various major projects that risk to encroach on their lands and disrupt their natural ecosystems (see Enbridge’s Northern Gateway pipeline proposal and the Kinder-Morgan proposal) are standing on stronger legal grounds than ever before in their history. The B.C. and federal government are currently negotiating some 100 land claims by native groups across Canada.