Climate Change

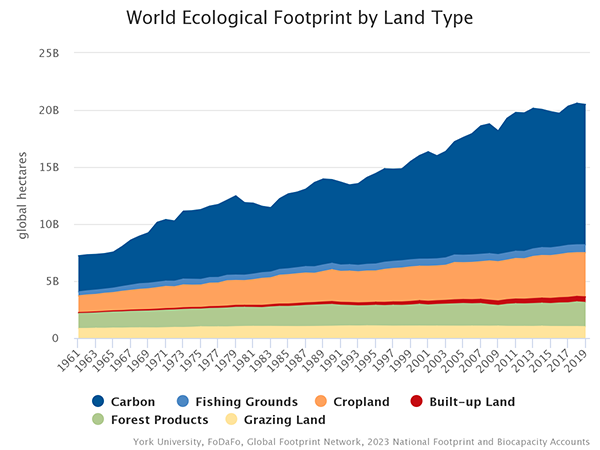

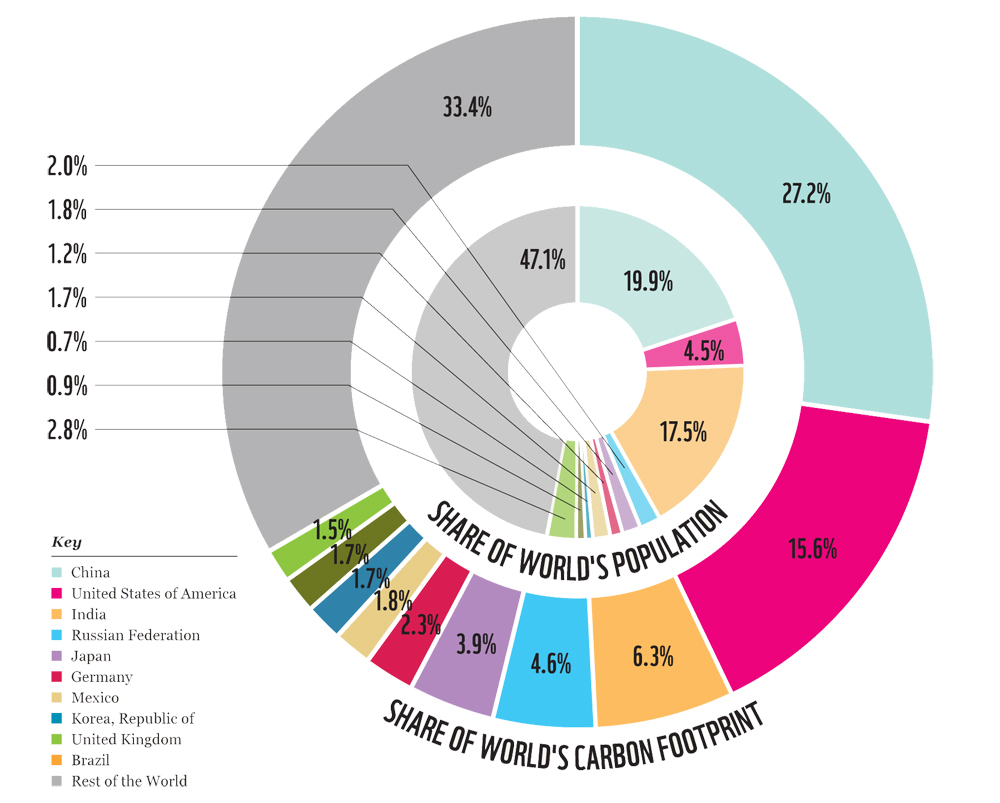

The Ecological Footprint framework addresses climate change in a comprehensive way beyond measuring carbon emissions. It shows how carbon emissions compare and compete with other human demands on our planet, such as food, fibers, timber, and land for dwellings and roads. Carbon Footprint

Carbon Footprint

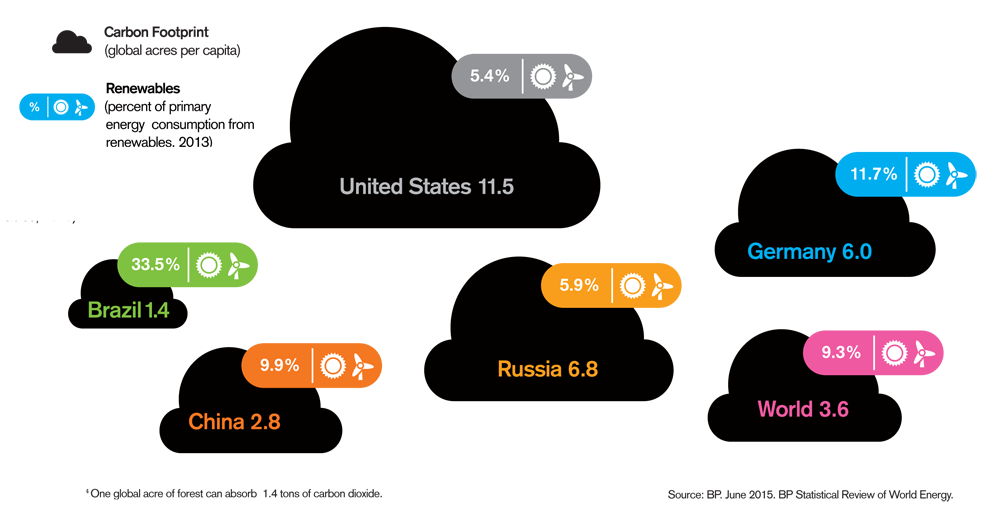

Today, the term “carbon footprint” is often used as shorthand for the amount of carbon (usually in tonnes) being emitted by an activity or organization. The carbon footprint is also an important component of the Ecological Footprint, since it is one competing demand for biologically productive space. Carbon emissions from burning fossil fuel accumulate in the atmosphere if there is not enough biocapacity dedicated to absorb these emissions. Therefore, when the carbon footprint is reported within the context of the total Ecological Footprint, the tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions are expressed as the amount of productive land area required to sequester those carbon dioxide emissions. This tells us how much biocapacity is necessary to neutralize the emissions from burning fossil fuels.

Measuring the carbon footprint in land area does not imply that carbon sequestration is is the sole solution to the carbon dilemma. It just shows how much biocapacity is needed to take care of our untreated carbon waste and avoid a carbon build-up in the atmosphere. Measuring it in this way enables us to address the climate change challenge in a holistic way that does not simply shift the burden from one natural system to another. In fact, the climate problem emerges because the planet does not have enough biocapacity to neutralize all the carbon dioxide from fossil fuel and provide for all other demands.

This framework also shows climate change in a greater context—one which unites all of the ecological threats we face today. Climate change, deforestation, overgrazing, fisheries collapse, food insecurity, and the rapid extinction of species are all part of a single, over-arching problem: Humanity is simply demanding more from the Earth than it can provide. By focusing on the single issue, we can address all of its symptoms, rather than solving one problem at the cost of another. Also, it makes the self-interest to act far more obvious.

The carbon Footprint is currently 60 percent of humanity’s overall Ecological Footprint and its most rapidly growing component. Humanity’s carbon Footprint has increased 11-fold since 1961. Reducing humanity’s carbon Footprint is the most essential step we can take to end overshoot and live within the means of our planet.

Paris Climate Agreement

The climate pact approved in Paris in December 2015 represented a huge historic step in re-imagining a fossil-free future for our planet. It is nothing short of amazing that nearly 200 countries around the world—including oil-exporting nations—agreed to keep global temperature rise well below 2 degrees Celsius and, to the surprise of many, went even further by agreeing to pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

These bold moves suggest an end to fossil fuel use well before 2050. That is within 31 years— within many of our lifetimes. The math is simple: we know from IPCC’s 2014 report that a concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere of 450 ppm CO2equivalent gives us a 66% chance to comply with the Paris Agreement’s 2-degree Celsius (2°C) goal. In contrast, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of the United States Department of Commerce (or NOAA) reports that in 2022 we were already at 523 ppm CO2equivalent. This confirms the need to rapidly end emitting carbon from fossil fuel, while also scaling up sequestration.

In contrast, the pledges submitted by each nation are projected to result in a temperature rise of between 3 and 7 degrees Celsius, exceeding the 2-degree limit or “global handrail” acknowledged by the agreement. The final agreement requires countries to return every five years with new emission reduction targets. Whether this essential requirement will be sufficient to catalyze more action remains to be seen.

The agreement itself implies that committing to the 2-degree limit will involve far more than just a transition to clean energy; managing land to support many competing needs also will be part of the solution. If we truly move out of fossil fuel fast and furiously, demand for substitutes—for instance forests as a fuel source—could place tremendous new pressures on our planet if not managed well. At the same time, the agreement references reducing emissions through “sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries.” The agreement also says it “aims to strengthen the global response to climate change…in a manner that does not threaten food production.”

The combination of all these forces—consumption, deforestation, agriculture and food, emissions—underscores more than ever the value of a comprehensive measure like the Ecological Footprint that takes into account all competing demands on the biosphere, including CO2 emissions and the capacity of our forests and oceans to absorb carbon.

Renewable Energy

Still, transitioning to renewable energy is one of the most powerful ways for a country to reduce its Ecological Footprint. Many countries still have a long way to go on that front.