The United Nations launches global goals to achieve humanity’s collective dream: sustainable development

This week marks an extraordinary moment for humanity. Representatives of 193 nations are convening in New York at the United Nations to launch the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These goals lay out the conditions we need to secure great lives on this one planet for all, regardless of income level, gender or ethnicity.

At a time when global economic uncertainty and human tragedy dominate the news cycle, this unique opportunity to bring the universal dream of sustainable development to the forefront of public attention worldwide is definitely worth celebrating.

We are pleased that the UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre has proposed the Ecological Footprint as an SDG metric for Goal 12.2: “by 2030 achieve sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources.”

And we can’t help but ask the following question: How do we know whether all the SDG activities generate sustainable development? With the United Nations on the verge of adopting sustainable development as its central agenda, how do we know whether all the potential activities on the 169 goals are adding up to sustainable development?

Resource security as the foundation for sustainability

“Development” is shorthand for committing to well-being for all. “Sustainable” implies that such development must come at no cost to future generations. In other words, development is required to occur within what the planet’s ecosystems are able to provide season after season, year after year. It needs to be enabled within the means of nature.

This principle was put forward by the possibly most tangible definition of sustainable development ever given: “improving the quality of human life while living within the carrying capacity of supporting eco-systems,” in the 1991 report “Caring for the Earth” jointly issued by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the U.N. Development Programme (UNDP) and WWF.

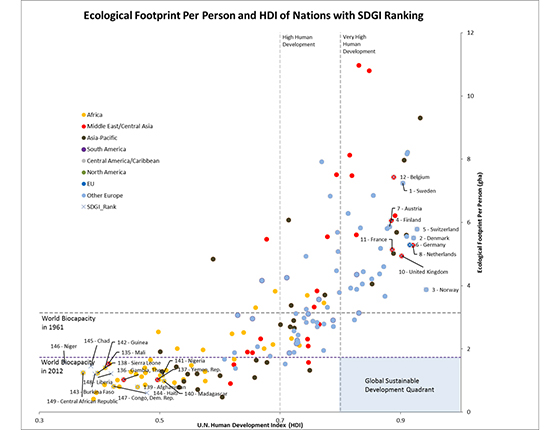

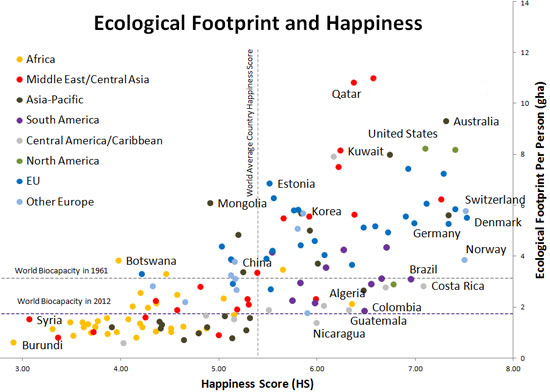

The goal of “well-being for all” has its own UN-supported metric: the Human Development Index (HDI), which was created by Indian economist Amartha Sen, with his Pakistani colleague and former finance minister Mahbub ul Haq, to provide an alternative to national income as a standard of development. HDI is based on the life expectancy, education and income of a nation’s residents. On a scale of zero to one, UNDP defines 0.7 as the threshold for a high level of development (0.8 for very high development).

The requirement “within the means of nature” is tracked by the Ecological Footprint. At current population levels, our planet has only 1.7 global hectares (gha) of biologically productive surface area per person. Thus, the average Ecological Footprint per person worldwide needs to fall significantly below this threshold if we want to accommodate larger human populations and also provide space for wild species to thrive.

All of us want high HDIs for everybody AND we need to make sure we stay within the regenerative capacity of the planet. These two thresholds define two minimum criteria for global sustainable development—an average Footprint (significantly) lower than 1.7 gha per person and an HDI of at least 0.7. Each nation’s endowment and ability to trade vary enormously. However, to achieve global sustainable development, humanity’s demand, at current population levels, has to fall below an average of 1.7 gha per person.

Ecological Footprint and Human Development Index, 1980-2011

Special thanks to Sustainable Growth Associates for their work on this animated graphic..

Is it possible to provide high human development within our planet’s resource budget?

Eight countries have shown us it is possible, according to the latest data (2011). Algeria, Colombia, Ecuador, Georgia, Jamaica, Jordan and Sri Lanka show “high human development” (as calculated by the United Nations) with a resource demand (Ecological Footprint) that could be extended to every world citizen. One nation, Cuba, even achieves “very high human development” (its HDI ranks in the top 35 countries among 170 featured; see below) while keeping its resource demand per person lower than per-person global biocapacity.

Resource risk is acute for 71 percent of the global population

Growing population and increasing consumption per capita continue adding pressure on ecological constraints and contributing to climate change, compounding resource risks for every country’s economy. Such risks are most evident in countries with ecological deficits—consuming more than their ecosystems can provide—and low income, making it more difficult for them to buy themselves out of resource scarcity. A staggering 71 percent of the world population now lives in countries with this double challenge: an ecological deficit AND lower-than-world-average income. That is up from less than 15 percent of countries in the early 1960s.

This reality leaves humanity with a pressing question: How can nations—both high and low income—make their development achievements last, if their development model depends on more than what the biosphere is able to renew?

History and Applications of HDI-Footprint Framework

French researcher Aurélien Boutaud first raised this issue in 2002. He introduced the HDI-Footprint relationship as an “embarrassing truth” of the sustainable development challenge. The current development model, in which development gains still come at the cost of increasing Ecological Footprints is one, he claims, in which “all lose.”

UNDP’s Human Development Report 2013 echoed his concern exactly, stating that “progress in human development achieved sustainably is superior to gains made at the cost of future generations.” It used the double-metric HDI-Ecological Footprint (Fig. 1.7) to back up this very point.

Other international and national decision-makers have turned to the HDI-Footprint framework to illustrate the challenge of sustainable development:

- The U.N. Environment Programme’s Green Economy Report 2011

- The 7th Environment Action Programme (EAP)

- Most recently, India’s environment minister Prakash Javadekar criticized high-income countries’ lifestyles for being “unsustainable” while speaking at a global forum on climate change.

- Last but not least, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development’s cornerstone Vision 2050 report calls for a new agenda for business.“Achieving Vision 2050 will require a radical but feasible transformation of global markets, governance and infrastructure, and a re-thinking of our ideas of growth and progress,” states the report.

Bringing about sustainable development around the world is daunting but not impossible. While we still have far to go, measuring the basic conditions of sustainable development (well-being and living within nature’s means) can certainly help us navigate our path. We’re energized by the shared vision that the SDGs give us over the next 15 years and look forward to contributing our efforts so that the process unfolds within the means of our one planet.

From global to local: India villages apply HDI-Footprint framework

Just as the Sustainable Development Goals set targets for national governments around the world, many development organizations seek metrics to measure their sustainable development achievements. One such organization is IDE-India (IDEI), a nonprofit that works to eradicate poverty with small-holder farming communities. This year, IDEI and Global Footprint Network piloted a tool that measures the Human Development Index (HDI) and Ecological Footprint of villages in Odisha, India. By calculating HDI and Ecological Footprint for several villages where IDEI has projects, we can show a snapshot of each community’s development and natural resource conditions.

Just as the Sustainable Development Goals set targets for national governments around the world, many development organizations seek metrics to measure their sustainable development achievements. One such organization is IDE-India (IDEI), a nonprofit that works to eradicate poverty with small-holder farming communities. This year, IDEI and Global Footprint Network piloted a tool that measures the Human Development Index (HDI) and Ecological Footprint of villages in Odisha, India. By calculating HDI and Ecological Footprint for several villages where IDEI has projects, we can show a snapshot of each community’s development and natural resource conditions.

Though it is still early in the application of the tool, preliminary results indicate that IDEI treadle pumps—human-powered water pumps that provide additional irrigation water during dry seasons—increase income (a component of HDI) and biocapacity (biologically productive land surface) but also increase the Ecological Footprint, though only marginally. In other words, the pumps increased the villagers’ resource availability, ultimately enabling them to improve their living conditions.

The villagers use the information about their HDI and Footprint in a different way—by taking the knowledge they gain from workshops on natural resources to construct an image of their ideal village. In time, and by conducting pre- and post-assessments, we hope to demonstrate that sustainable development is more effective than conventional development in securing human well-being. With these tools we hope to inspire other communities and social entrepreneurs around the world to adopt a similar approach.